Our biometrics are captured, measured and stored. Does it mean that personal privacy will become a relic of the past?

Panopticon Modality

Perhaps, our privacy has never been so fragile as it is today, even though countless security solutions are advertised on every corner. And while the dimension of social media is slowly and painfully drifting towards at least some degree of user respect, new threats are popping up.

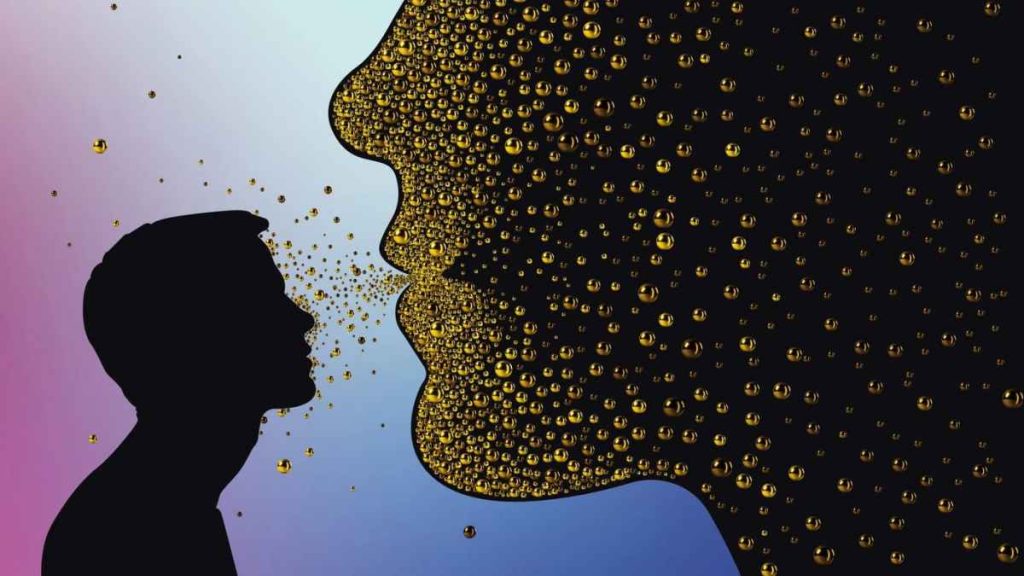

It’s not just our private data — address, personal contacts, shopping habits — that are at risk. Our very anatomy is turning into a major weak point as our biometric parameters are carefully gathered, measured and preserved for later use. Sometimes it gets leaked, and then we can fall victim to biometric spoofing.

This modality was, perchance, first foreseen in a mystical epiphany by Jeremy Bentham. During his visit to the Russian Empire — the same country that will spawn a constellation of prisons named GULAG later — he envisioned a new prison concept. A prison, which was entirely constructed of some transparent building material.

In such bizarre penitentiary inmates could be observed 24/7 together with guards. Bentham named his concept Panopticon— all seeing in Greek. With that idea he idealistically hoped to solve a millennium-old riddle of who guards the guards and make the penitentiary system more humane by being publicly observable.

All of a sudden, something similar to Panopticon is appearing today as we are constantly under observation by surveillance, trackers, scanners, and sensors. This paves the way for some major problems.

Problem #1: It springs a leak

Nobody likes being spied on: that’s why we are averted by the connotation of the word ‘stalker’. Even if it’s the government or a smartphone maker forcing us in a soft manner to accept the legal mumbo jumbo of user agreements and other byzantine examples of bureaucracy.

But things get even worse when all this precious data leaks like applewine from a cracked old barrel. And instances of data leakages aren’t a rarity at all. Have you heard of Aadhaar? This is the world’s largest biometric database, ambitiously gathered in India, with about 1.3 enrolled users.

It stores essential data — like fingerprints and iris — which are used to create a citizen’s unique profile. Based on this info, they receive an individual ID number consisting of 12 digits — a sacred number as some Hindu deities have 12 names.

In 2018 Tribune of India made an explosive sensation by claiming that access to Aadhaar’s treasure could be bought on WhatsApp for a reasonable price of 500 rupees ($6.28). Probably 6 bucks wouldn’t grant access to the entire database, but rather a regional subdivision: village, small town, city’s neighborhood.

From Asia’s heart to the West, the situation still remains disappointing, even though the scale isn’t that gargantuan. In the UK, a company named Suprema lost data of one million people. And it was a whole enchilada: fingerprints, facial parameters, unencrypted names.

And just recently TikTok found itself amidst a topsy-turvy caused by an alarming claim that personal data of almost 2 billion users — nearly twice as much as Aadhaar’s database — was hacked and stolen. Someone under the alias AgainstTheWest proudly demonstrated screenshots of an allegedly hijacked data repository. TikTok called it a bluff, however.

Problem #2: It breeds doppelgängers

Having the private data leaked — which includes bodily parameters — is just half the problem. Things get worse when the sinister tech, that allows copying virtually any of the biometric traits that we have, enters the stage. They include voice, fingerprints, handwriting, your lovely face, and even the way you type on a keyboard.

Mischief-makers lurking online can snatch and replicate them. It’s called spoofing, not hacking, and it has many creative techniques. For instance, a copy of your fingerprints can be retrieved from a photo where your fingertips are clearly visible. Then their patterns will be extracted and imprinted on gelatin or latex and voilà: culprits own a piece of you.

And hijacking a voice is even simpler. All they need is a caboodle of your voice messages from Telegram or a recorded 20-minute phone conversation to amass enough training material to teach a neural network — like SV2TTS — to copy your voice 1:1.

Problem #3: It jeopardizes your wellbeing

Your copied biometric becomes a weapon of the so-called Presentation Attacks (PAs). They are called this way because a fake part of your personality — face, voice, signature — is presented to a security system for the sake of making it to believe that it’s you knocking on its doors.

But spoofing isn’t limited to PAs only. A human vis-à-vis is even more gullible than a heartless machine as practice shows. It is known that the human voice can evoke implicit trustworthiness attributions from a person who hears it — we are naturally prone to trust the fellow humans after all, sadly.

And now imagine what sort of havoc can be raised if someone clones your voice and bombards your family, colleagues, friends, and business partners with disinformation or money pleas?

Staying Alive

Perhaps, the only solution that can solve this dilemma is deepfake detection. Even though our faces and voices can be stolen and falsified, there’s a thin line of expertise that separates us from the spoofing chaos. And again, it’s operated by AI.

On our side we have a bunch of good robots, so to say, who know how to tell a fake from a real thing. They analyze a rich repertoire of anatomical parameters: the way the airflow goes through your vocal cord and nasal passages to form a voice, the patterns of whorls and ridges in your fingerprint and even the speed of your keyboard pecking.

Together, these parameters are known as liveness. This idea has been postulated by Dorothy E. Dennings in the early 2000s. In her work, she described a concept that shares similarities with a Turing test. A person must be able to prove that they are alive before they can access a system.

Eventually, this modality can replace logins and passwords for good. So, to quote Bee Gees, let’s stay alive to avoid spoofing for good.